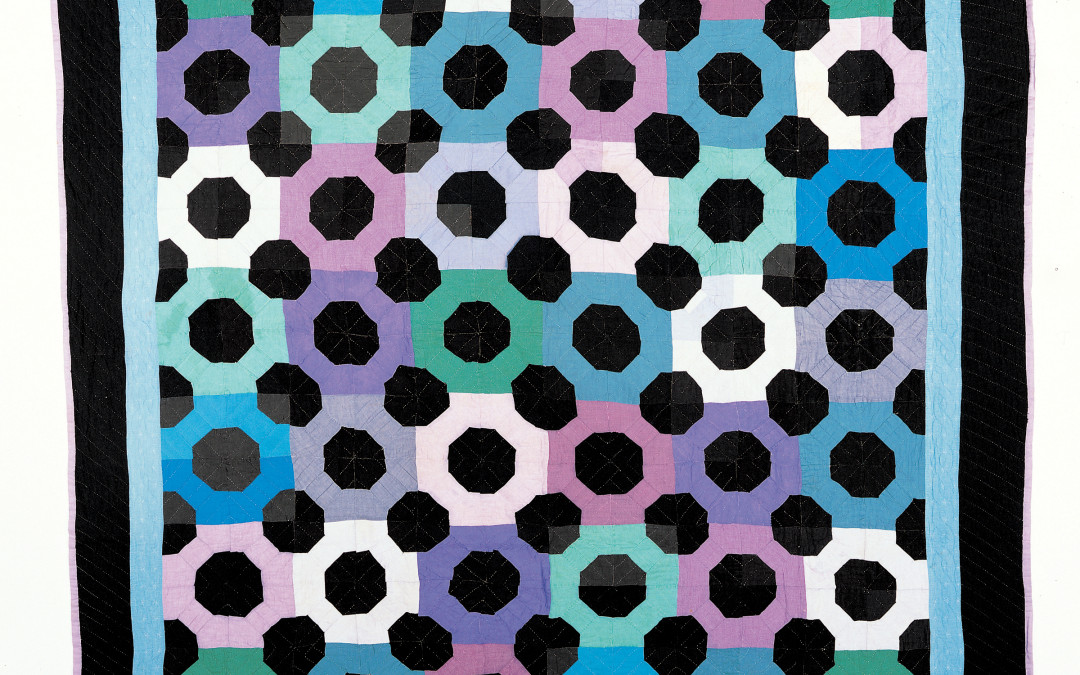

BowtieHolmes County, Ohioca. 1930 Cotton and synthetic fiber85 x 75 in.

Copyright © Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Victor Vasarely and the Amish might initially seem like an incongruent pairing, never mind Paul Klee, Piet Mondrian, Josef Albers, or Mark Rothko.

But it’s hard not to find amazing commonality between these vanguards of modernist, abstract painting and the intricate quilts created by a group we often stereotype as either plain-living or perhaps simply just plain.

However, far from the “black on black” that you might expect, what immediately strikes visitors to Amish Abstractions: Quilts from the Collection of Faith and Stephen Brown—currently on display at the de Young Museum in San Francisco—is the almost slap-across-the-face boldness of the designs that feature a combination of sophisticated geometric patterns with a broad and saturated palette.

Not surprisingly, this was essentially the reaction of the Browns when they first encountered an exhibition of Amish quilts at the Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery in Washington, D.C. in 1973. Since then, the San Francisco-based couple has enthusiastically built one of the most important antique Amish quilt collections in private hands, with outstanding examples from communities throughout Pennsylvania and the Midwest.

An insular and devoutly conservative branch of Anabaptism (a Protestant sect that emerged in Europe during the early 16th century), the Amish confer greater value in community than with the individual, going so far as to shun activities and possessions that might be interpreted as prideful.

Which makes the Brown’s collection of Amish quilts, created at the peak of the tradition between 1880 and 1940, all the more intriguing, for, with each quilt, we get an unexpected peek into this remarkable community.

The quiltmakers themselves never considered their work as art. Learning the craft initially from their “English” neighbors—as the Amish referred to all outsiders—Amish women created these bedcovers primarily as gifts for children leaving home on their wedding days, after which they would commonly be passed along as cherished heirlooms from one generation to another.

Furthermore, the design of the quilts strongly represented the values of the respective communities. Amish quiltmakers, for instance, pieced together material instead of using the more common and fashionable approach of appliqué, thereby reflecting the community creed that encouraged thrift. Of course, it’s precisely this emphasis on piecing that leads to the strong geometric arrangements.

The selection of the 48 quilts on display, from the Brown’s collection of 110, provides a representative sampling spanning both geography (from Lancaster Country in Pennsylvania to Ohio and beyond in the midwest) and form (multiple examples of Ocean Waves, Triangles, Roman Stripe, Tumbling Blocks, and Double Wedding Rings, among others, are shown).

Fortunately, the exhibition itself employs a clever bit of spatial geometry to allow viewers to more easily discern and compare the various quilts. Through this, it’s readily obvious that the Amish, while appearing uniform to outsiders, are, in reality, a complex and diverse set of communities, each with its own interpretation and application of aesthetics and standards.

We see this most clearly, for example, by the lack of a single set of criteria guiding quiltmaking. Instead, quiltmakers in each community draw individually from surrounding neighborhoods and influences, all while maintaining the principles and norms of their tightly structured societies.

So, in the end, how are we to judge Amish quilts as art? Quiltmaking scholars Robert Shaw and Joe Cunningham offer complementary advice in the catalog that accompanies the exhibition.

Shaw writes, “Along with certain other American quiltmakers, the Amish were among the first people in the world to create works of modern visual abstraction…However, comparisons [with modernist painters] are problematic. Where modern artists sought to strip their work to its most basic elements, eliminating representational context to allow color and form to speak for themselves, the Amish had no need for such divestment.”

Shaw continues, “The women who made the quilts included in this exhibition lived in a world that was already stripped bare of self-involvement, pride, and even the need to create self-conscious works of art. The quilts were made by believers, not seekers.”

Cunningham, however, suggests approaching the quilts from a dual perspective, writing, “Of course, the quilts are, in fact, large, abstract compositions and we can view them as such, considering their aesthetic merits and judging them on the basis of their graphic strength. But we can also study them as part of an American tradition.”

The question of tradition or art, notwithstanding, it’s clear the Amish abstractions more than hold their own against Vasarely, Mondrian, or whoever else you might want to stand in comparison.

Plan Your Visit

Amish Abstractions: Quilts from the Collection of Faith and Stephen Brown is on display at the de Young Museum, 50 Hagiwara Tea Garden Drive in the heart of San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park from November 14 to June 6, 2010. Along with the exhibition, an adjacent learning center offers children and others an interactive, hands-on introduction and exploration to quilt geometry and patterns.

Admission

The de Young is open Tuesday through Sunday, 9:30 a.m. to 5:15 p.m. Adults $10, Seniors 65 and over $7, Youths 13-17 $6, College Students with ID $6, Children 12 and under FREE.