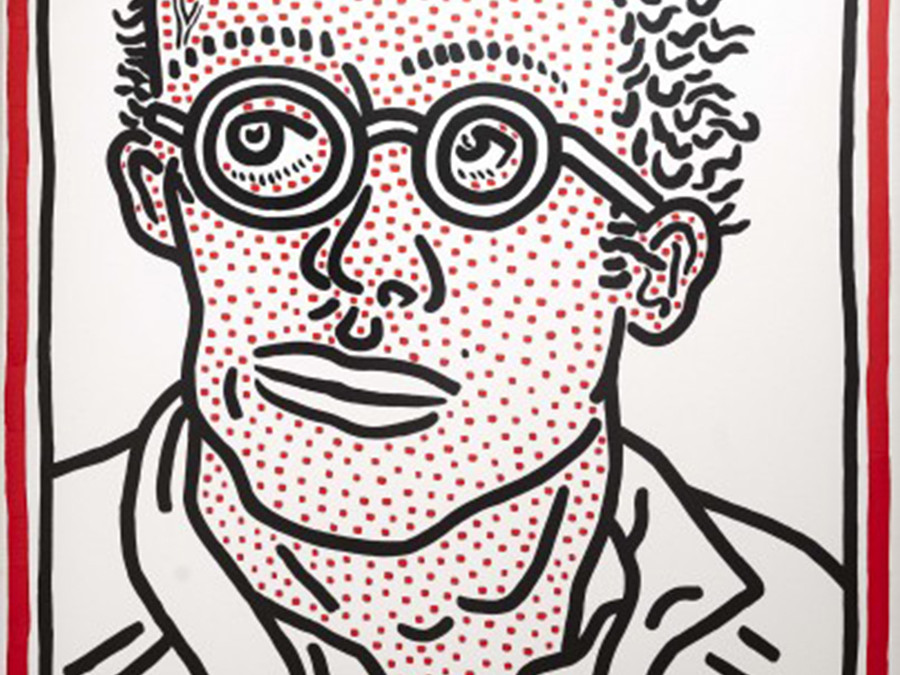

Keith Haring, Untitled (Self-Portrait), 1985. Acrylic on canvas.

© Keith Haring Foundation

In the early 1980s, New York City was dirty, dangerous, and just a few years out from the brink of bankruptcy. To many, the city seemed in shambles, an unrecognizable shell of its once-vibrant former self.

But to the thousands of creative souls drawn to Gotham—ironically, in part, because of the lure of cheap rent—the city offered an exciting escape from an even-more malfunctioning world, together with the opportunity to discover and define new types of art and ideals.

These artists, writers, musicians, and filmmakers—along with an energetic class of club kids who considered themselves to be any or all of the above—could, in some sense, be considered the proto-Makers of their day, fashioning new designs and creations from the ignored, discarded, and the ordinary.

From this expressive milieu came musicians such as Debbie Harry, David Byrne, and Madonna, filmmaker Jim Jarmusch, and wunderkind Glenn O’Brien, who’s influential cable access show, TV Party, helped chronicle the bewildering scene (while, at the same time, adding to the disarray).

In the art world, unique talents such as Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring were similarly set to take art in a new and distinctly post-Pop direction. Informed by the sensibilities of the ubiquitous graffiti they saw around them—and to which they also contributed—this new generation of artist turned the spotlight from the artifacts of our culture (think products and advertising) to focus instead on the basic meaning of the symbols and conventions that shape our thinking.

Basquiat was forceful and direct, at times angry, at other times richly nuanced. Haring, on the other hand, was more playful, engaging without threatening, airy while purposeful. Between the two, Haring’s work can sometimes appear more accessible.

A comprehensive exhibition currently underway at the de Young Museum offers an opportunity to see some of Haring’s earliest and most socially provocative work. Featuring works on loan from the Keith Haring Foundation, along with crucial supplementary loans from both public and private collections, the exhibition represents the first major Haring show on the West Coast in nearly two decades.

Born in 1958 in Reading, Pennsylvania, Haring was raised in neighboring Kutztown, showing interest in art and drawing at an early age. After hitchhiking across the country in his late teens—including a stop in San Francisco—Haring settled in New York City with the intention of studying painting at the School of Visual Arts in Chelsea.

Located on the edge of the burgeoning downtown arts and club scene of Greenwich Village, SoHo, and Canal Street, the school provided the perfect base for Haring to discover and explore the power of public art. In the process, Haring quickly developed his own unique vocabulary of iconic symbols, including radiant babies, barking dogs, encroaching spaceships, and allegorical pyramids, among others.

Perhaps not surprisingly, some of Haring’s earliest work appeared in the city’s subway system, but not where you might expect. Noticing black paper panels on the station walls—temporary placeholders for expired advertising—Haring energetically composed hundreds of chalk drawings between 1980 and 1985 (enduring arrest on more than one occasion).

Impressively, you can see several of these early subway drawings at the de Young exhibition, among the more than 130 compositions on display. Other works include large-scale paintings on tarpaulins and canvases, a series of studies on paper and bristol board, and sculptures expressed on various media (including a 1963 Buick Special).

Even San Francisco’s city-commissioned sculpture Untitled (Three Dancing Figures) is present, temporarily moved from its regular home on the corner of Third and Howard Streets and placed near the entrance of the de Young.

In all of Haring’s work, we find a distinctive use of bold and authoritative lines, richly contrasting colors, and active representation, often using radiating lines for both animate and inanimate objects. More than many artists of his time, Haring attacked difficult social, cultural, and political issues—ranging from sexual and racial inequality, nuclear proliferation, and economic and environmental injustice—deftly camouflaging complexity through figurative simplicity.

In this way, Haring seemingly never left his roots. For Haring, the goal was always to deliver the message to a hurried public, efficiently and economically, whether in a gallery or museum, or momentarily on a subway platform.

Plan Your Visit

The exhibition is on display until February 16th.

de Young Museum

50 Hagiwara Tea Garden Drive

Golden Gate Park

San Francisco, CA

Open Tuesdays through Sundays: 9:30 am to 5:15 pm

deyoung.famsf.org